Akiko Suwa-Eisenmann, Chairperson of the HLPE-FSN presenting the background note for the Committee on World Food Security’s High-Level Forum, on 12 May 2025, in Rome, Italy, titled Tackling Climate Change, Biodiversity Loss and Land Degradation through the Right to Food.

©FAO/HLPE-FSN Silvia Meiattini

The HLPE-FSN Chairperson, Akiko Suwa-Eisenmann, opened the Committee on World Food Security’s High-Level Forum “Tackling climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation through the Right to Food” on 12 May 2025, in Rome, Italy, by pointing to a significant gap in global policy thinking. “Since the HLPE-FSN report on ‘Climate change and food security’ thirteen years ago, there has been an accumulation of evidence on the impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation on food security. Yet, we lack a comprehensive synthesis on the evidence and the policies that address simultaneously the environmental challenges and food security in all its dimensions.”

Professor Suwa-Eisenmann presented the HLPE-FSN background note for the High-Level Forum, emphasizing how while international environmental frameworks have advanced in ambition, a rights-based approach remains largely absent.

The note explains that “a legal analysis reveals gaps in translating the objectives of the Rio Conventions into tangible protections for the right to food.” Yet, there is hope: “even if the Rio Conventions do not integrate the right to food, national plans can and sometimes do. The CFS could play an important role in this direction by highlighting the relevance of the right to food for coherence across the implementation of the Rio conventions and adopting a food systems approach in order to achieve both the environmental objectives and the right to adequate food,” Suwa-Eisenmann clarified.

To illustrate this potential, she described how “the evidence on the impact of environment on food security is summarized by international Science and Policy Interfaces.” The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), for instance, “covers the impacts of climate change on food production, from agriculture to food security and food systems. It addresses the linkages between food security, desertification, land degradation and greenhouse gases.” Meanwhile, “the IPBES, established in 2012, has written for instance a report on the role of pollinators on food production (2016) and last year, on the nexus between food, health, water and biodiversity, proposing solutions.” The Science-Policy Interface of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) “stresses the role of sustainable land management for well-being and livelihoods,” and “the HLPE-FSN itself has worked on climate change in 2012, and on related topics such as fisheries (2014), water (2015), forestry (2017), and is preparing now a report on Building resilient food systems.”

These environmental crises - climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation - are deeply interconnected and have far-reaching impacts on food systems. “Climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation feed each other, and have ‘cascading impacts’ on food systems and people.” These include “increasing temperature, erratic rainfalls, changing distribution of pests and diseases, and more frequent extreme weather events,” all of which “modify the ecosystems, more and more. This impacts crops, livestock, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture, not only the quantity of food, but also its safety and its nutritional content. This will also translate on prices, affecting the incomes of producers and workers along the supply chain and the consumer’s access to food.”

The HLPE-FSN Chair reminded participants that not all are impacted equally. “Vulnerability is particularly high in some areas, such as the small Pacific islands, and for some groups, compounded by non-environmental factors, such as gender, age, rurality, type of employment, or being part of a marginalized group, such as Indigenous Peoples or pastoralists.”

She noted that “land use is central to climate action, biodiversity, and the right to food.” While land-based measures “have a considerable mitigation potential,” they must be designed carefully. “Global modelling studies suggest that mitigation measures such as a carbon tax on agriculture and land use changes could raise prices and increase hunger by 2050 more than climate change itself.” Similarly, while “conservation policies, such as creating protected areas, can simultaneously advance biodiversity, climate adaptation, and mitigation,” they must not threaten “local communities who often use these areas for food, firewood and grazing.” Top-down conservation risks undermining “communal resource management, of forests, rangelands, or fisheries,” which “often outperform” imposed approaches.

What’s needed, she argued, is “to find the right balance between environmental protection and livelihoods.” She invoked the Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries model, by economist Kate Raworth[i]: “preserving the nine Planetary boundaries, the safe environment in which humanity has lived for the past 10 000 years (of which six are already transgressed, with a key role of food systems in five of them).” But equally important is “preserving the social foundation for a life of dignity, the inner circle, among them food and health.” For that, “the right to food is a powerful ally.” First recognized in 1948 and made legally binding in 1966, it is now explicitly recognized in over 30 constitutions. “The Voluntary Guidelines on the right to food provide guidance, linking food security to human rights principles of accountability, participation and non-discrimination,” she explained.

The HLPE-FSN Chairperson then explored how each of the three Rio Conventions interacts with the right to food. “The three Rio Conventions, on climate, biodiversity and desertification, focus on their environmental objectives but their work intersects with food security. However, the original texts of the conventions do not explicitly mention the right to food.

Despite references to food security in the Paris agreement of 2015, the UN framework convention on climate change lacks enforceable human rights safeguards. As a result, climate action still tends to prioritize emissions over equity, often overlooking the rights and needs of the most affected.” The Un Convention on Biological Diversity (OCB) “does not explicitly mention the right to food, but implicitly supports it,” and yet “implementation gaps persist,” with national biodiversity strategies “frequently failing to integrate human rights and often excluding community participation.” The UN Convention to Combat Desertification also “does not refer to human rights protections,” but COP14 in 2018 encouraged application of the CFS Voluntary Guidelines on Tenure.

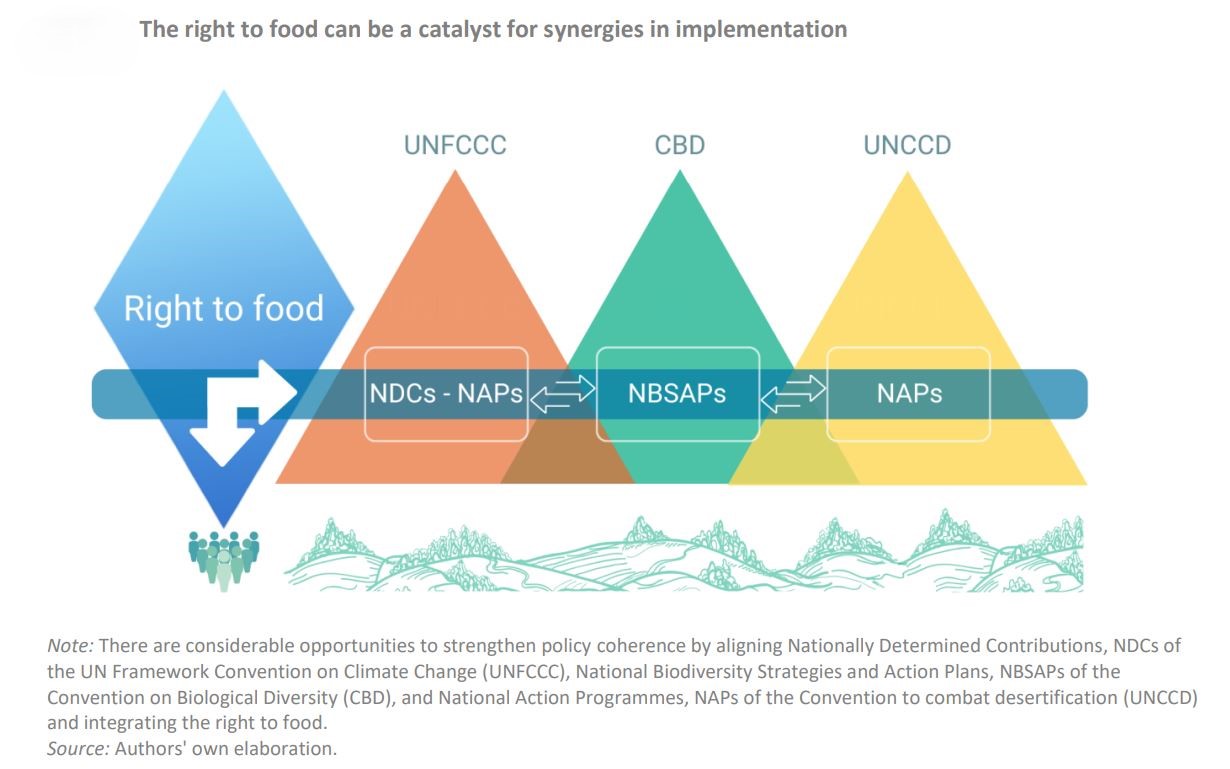

But change is possible. “Against this backdrop, there are considerable opportunities to strengthen policy coherence by integrating rights-based frameworks in the National plans under the three Rio conventions. These plans are becoming more inclusive and participatory. They could support policies so that smallholders and workers in the food systems benefit from climate mitigation measures, providing them with financial resources. Recognizing the right to food can also lead to more equitable and more efficient environmental policies,” Suwa-Eisenmann stated.

She closed her address with four key messages for action: “the Right to food can be a unifying solution to harmonize the objectives of the Rio conventions.”

Therefore, “instruments and policies aiming to address climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation must incorporate the right to food along the entire food systems, and not only production.”

She also reiterated the “need for an updated synthesis of evidence on the compounded impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation, as well as of the policies implemented to address these challenges, on food security and nutrition and the progressive realization of the right to food.”

Finally, she concluded highlighting the opportunity for the CFS, that, in her words, “should highlight the relevance of the right to food as a strategic nexus for enhancing coherence across the implementation of the Rio Conventions, facilitate evidence-based policy design and the sharing of experience, for food security and nutrition in a sustainable planet.”

[i] in her book "Doughnut Economics" Kate Raworth criticizes that our economical acts and decisions are based on the economic theories of the 1960s, which are mainly focused on a continuous and infinite growth. She suggests an update to the 21 st century economy, which accounts not just for our well-being and prosperity, but for that of our planet as well. To make the missing factors in classic economies visible, she developed a "Doughnut Model", which includes twelve aspects of our social foundation, as well as nine planetary boundaries and explains that the ideal space of our economy is between these two elements.

Raworth, K. 2017. Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. New York, USA, Random House. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340685996_Kate_Raworth_-_Doughnut_Economics_Seven_Ways_to_Think_Like_a_21st_Century_Economist_2017

Referencing the paper: HLPE. 2025. Tackling climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation through the right to food – Background note for the Committee on World Food Security’s High-Level Forum held on 12 May 2025, in Rome, Italy. Rome, FAO.